Oil prices should start to trend up in the second half of the year

For the global economy, the plunge taken by oil prices is the most striking phenomenon of the last six months. The plunge came as a real surprise to analysts and the financial markets, which had been expecting prices to stay close to US$100/barrel. Generally, this is good news for energy consumers, but the results could be more mixed for oil exporting nations like Canada. The Canadian dollar, interest rates and the return on some corporate securities are also feeling the impact. There is therefore reason to wonder about the future trajectory of crude prices.

Oil surplus

Most commentators attribute the current drop in prices to the surge in non-conventional oil production in the United States and a Saudi “plot;” however, the reality is somewhat more complex.

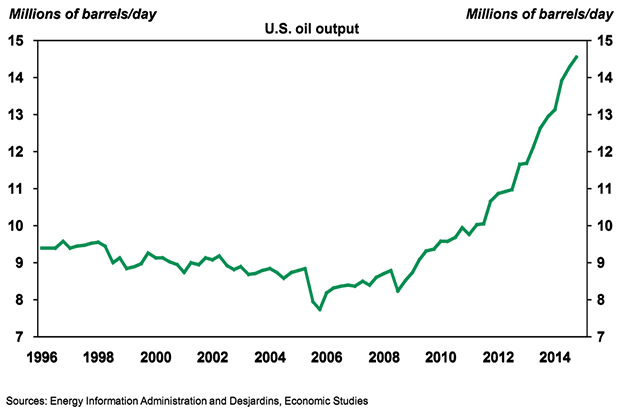

Yes, U.S. production has shot up, but the increase dates back further than mid-2014. It started in 2008 and hit a very impressive pace as of 2012 (graph 1). Combined with Canadian tar sands development, it created a situation in which the oil market was very well supplied and the slightest surplus posed a risk of destabilizing prices.

Usually, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) acts to regulate the market by adjusting its output. However, this adjustment relies mainly on Saudi Arabia, which decided to maintain its production to avoid losing market share. In addition, there were surprise increases in production from Libya and Iraq.

Simultaneously, the oil market surplus was intensified by economic problems in advanced nations in Europe and Asia, and slower economic growth in a number of emerging nations. This limited growth by global oil demand to about 0.7 mbd (millions of barrels a day) in 2014. Initially, the International Energy Agency (IEA) was anticipating growth of about 1.2 mbd.

Inelastic supply and demand

Prices adjust when an imbalance between supply and demand materializes. The problem with oil is that supply and demand are not very responsive to prices in the near term; as a result, it takes major price movements to prompt substantial adjustments in demand or supply.

In economic terms, for oil, supply and demand are said to be inelastic. For example, on the demand side, a big change in prices does not immediately change driver behaviour. On the supply side, the price correction has a big impact on investment in new oil production capacity, but the vast majority of producers will not shut down oil wells that are already in operation. Once all of the capital expenditures have been borne, existing wells still make a profit, even with lower prices.

Supply will adjust gradually

In the short term, oil production should keep growing and it will probably be the second half of the year before a bigger slowdown occurs. The IEA expects non-OPEC output to rise 0.8 mbd in 2015, much of it coming from the United States and Canada. This increase is less than half of that in 2014. Output from OPEC countries should tick up, primarily boosted by Iraq. All in all, global oil supply should rise by just under 1.0 mbd this year.

The longer-term supply adjustments could be much more substantial if prices stay where they are. Most of the fields outside OPEC and Russia are only profitable at more than US$50/barrel. Also, shale gas fields tend to be depleted quickly, and an investment deficit in this sector could trigger a faster response from the supply to the tumble by oil prices.

Demand sustained by better economic growth

Demand will play a critical role in price movements. Here, we can be more optimistic for 2015, as the United States will maintain a solid pace for economic growth, and the situations in Japan and the euro zone should improve.

However, much of the rise in demand will come from emerging nations. Doubts about China could persist, as economic growth there is flirting with 7%, rather than 10%; however, other emerging nations should make up for that. The potential for oil demand growth is still sizable in emerging nations, especially if we look at average consumption per capita. Comparatively, China and India are still far from seeing the boom in demand recorded in Japan in the 1970s, and Korea in the 1990s (graph 2).

A smaller oil surplus will open the door to a rise by prices

Overall, oil demand should go up about 1.3 mbd in 2015. As output should rise by just under 1.0 mbd, this will reduce the current surplus. In the near term, that will not keep global crude inventories from rising further, which should keep oil prices low for some time.

However, prices cannot stay low indefinitely without increasing the risk of an overly sharp adjustment to production. Growth by North American output could therefore give way to near stagnation as of 2016 if oil prices stay around US$50/barrel. As global demand should accelerate, fears of an oil shortage could quickly start to loom over the global economy again. Recently, this scenario prompted OPEC’s Secretary General to remark that an overly low price that discouraged investment paved the way for oil at US$200/barrel.

An earlier rise by oil prices, probably around the summer, would get the global market back to equilibrium and keep it there over the medium range. In the event of modest demand growth, it could be enough for oil to return to US$70/barrel by the end of 2016. On the other hand, if demand is more robust, it would take a surge to around US$90/barrel to encourage rapid development of costlier fields such as the Canadian tar sands.

Our core scenario is in the middle of that range. We expect to see oil return to an equilibrium price of about US$80/barrel in the next two years, which would foster an upswing by investment in Canada’s energy sector. The context will also favour a rise by the Canadian stock market and interest rates, as well as appreciation by the loonie.

Important: This document is based on public information and may under no circumstances be used or construed as a commitment by Desjardins Group. While the information provided has been determined on the basis of data obtained from sources that are deemed to be reliable, Desjardins Group in no way warrants that the information is accurate or complete. The document is provided solely for information purposes and does not constitute an offer or solicitation for purchase or sale. Desjardins Group takes no responsibility for the consequences of any decision whatsoever made on the basis of the data contained herein and does not hereby undertake to provide any advice, notably in the area of investment services. The data on prices or margins are provided for information purposes and may be modified at any time, based on such factors as market conditions. The past performances and projections expressed herein are no guarantee of future performance. The opinions and forecasts contained herein are, unless otherwise indicated, those of the document's authors and do not represent the opinions of any other person or the official position of Desjardins Group.