The Relationship Between Interest Rates and the Markets

On August 24, 2017, Mavis Wanczyk won US$758.7 million, the biggest lottery jackpot ever won by a single person in the United States. The odds of hitting Powerball's jackpot were only one in 292 million. To give you an idea, the new multimillionaire was more likely to be attacked by a shark, to make a hole in one shot at golf and be hit by a meteorite, all in the same day!

Knowing this, it seems foolish to try one's luck at the lottery. To counteract this problem, lottery organizers are banking on the "availability bias", which is our tendency to focus on the information that is available in our memory at the expense of a more rigorous analysis of the situation. To do this, they reserve the right to publish the name and photo of winners for advertising purposes, raising false hopes. Before making a decision, making a judgment or answering a question, it is therefore important to use a slower way of thinking that requires concentration. As you can guess, this advice also applies to the stock market.

In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, the 50 largest central banks reduced their key (short-term) interest rate more than 700 times. The aim was to stimulate economic activity, primarily by facilitating access to home ownership, reducing financing costs to encourage investment, regaining consumer and business confidence, and increasing risk-taking in the markets.

Of course, this strategy had the desired effect. The global economy is doing much better and the major markets are trading close to their historic highs. As stable and robust growth increases the likelihood of economic overheating that may result in inflation risk (widespread and uncontrolled price increases), interest rates will tend to rise to reflect the potential opportunity cost associated with weakened purchasing power. For example, the Bank of Canada raised its key rate three times since last summer (it is currently at 1.25%).

In recent years, a low interest rate environment has been associated with excellent stock market returns. Unfortunately, under the influence of availability bias, a large number of investors reduced their exposure to equities, under the pretext that a rise in interest rates would inevitably derail economic growth and jeopardize the upward trend in stock prices. However, as when buying a lottery ticket, you must take the step back to assess the situation. I invite you to read the concept of interest rate curve inversion.

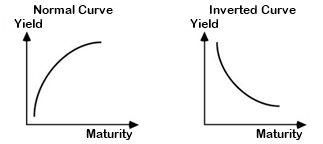

In an environment characterized by economic growth marked by low inflation (about 2%), the yields offered by the US government bond securities increase according to their maturity, what is called a "normal" yield curve, shown above. To compensate for the fact that a longer term exposes one to a greater risk of economic uncertainty, investors require a higher interest rate. In general this type of interest rate curve implies a low probability of recession, which bodes well for the stock markets. For example, over the past 50 years, the S&P 500 has grown 90% of the time outside of a recession.

When the curve is "inverted", that is to say; short-term interest rates are higher than long-term interest rates, the risk of recession is genuine. Since 1960, in the United States, this scenario has occurred on nine occasions and the economy has fallen into recession eight times. In general, this type of curve corresponds to a situation where a central bank is forced to abruptly raise its policy rate to counter higher inflationary pressures caused by a period of economic overheating, which inevitably creates a longer-term economic downturn.

Currently, the interest rate curve in the United States is "normal": the US (short-term) interest rate is 1.75%, compared to nearly 3% for the (long-term) ten-year US interest rate. As long as the curve is not "inverted", I invite you to remember this: a rise in interest rates does not change the world, except that one must ignore its first impression and adopt a more objective approach.